Kedar Hippalgaonkar, a scientist at Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR), together with his co-inventors, have found a metal that can conduct electricity without conducting heat, according to a press statement by A*STAR on March 21,2017.

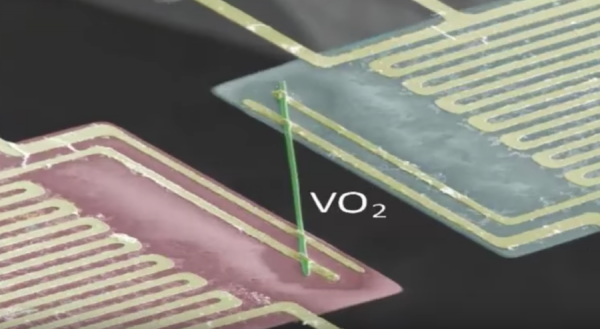

The metal is called vanadium dioxide, and this property makes it the first material in the world to defy a 164-year-old law of physics – the Wiedemann-Franz law – as its electrons conduct heat 10 times lesser than what is expected. The law states that good conductors of electricity are also good conductors of heat.

The study found that electrons in a nanobeam of the material move “in unison like a liquid” instead of moving as individual particles as they do in other metails like copper or iron at 67 degrees Celsius. Theoretically, this means that any device the metal coats will never go beyond the cap of 67 degrees Celsius.

This useful attribute of the metal can be tuned by adding impurities like tungsten to improve the temperature control property to “room temperature and lower”, said Dr Hippalgaonkar, who told TODAY on Wednesday, March 22.

With the metal acting like a “natural thermal switch”, the overheating problem in batteries and electronic device may become a thing of the past, he added.

The findings were published in the Jan 27 issue of scientific journal Science. Vanadium dioxide is a non-toxic and abundant metal and in this study is “100 times thinner than a strand of hair”, according to Dr Hippalgaonkar. With further tuning, it could replace bismuth telluride, a rare metal found in China that is “at least 10 to 100 times more expensive”, in applications like thermoelectric devices that can convert waste heat into power, he noted.

Moving forward, Dr Hippalgaonkar is working to discover more metals with the same Wiedemann-Franz law-defying property. “We are searching for other materials that are larger in size – not just nanostructures – where we can have a larger range of temperature control. Those might be closer to real-world applications,” he said.