One of the most spectacular folk art forms in India, with choreography drawn from folk and classical dance movements and martial arts, Purulia Chhau recently visited Singapore to take part in ‘A Tapestry of Sacred Music’ festival.

The event, held at Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay, brought together two Asian dance forms — Purulia Chhau from West Bengal, eastern India; and Kuda Kepang from Java, Indonesia — that unite communities and where the performers take on warrior personas. The performing troupes were Biren Kalindi Chhau Dance Ensemble and Kesenian Tedja Timur.

As part of the Esplanade event, Purulia Chhau was introduced to the Singapore audience by Sneha Bhattacharyya, a PhD scholar on this dance form and one of the people behind Banglanatak.com, an India-based organisation that makes social change through culture.

In an interview with Connected to India, Bhattacharyya said that promoting Purulia Chhau could empower the rural folk and also power tourism in eastern India, especially to the Purulia district of West Bengal. Purulia Chhau is one of the three main Chhau forms of eastern India, the other two being Mayurbhanj Chhau of Odisha, and Saraikela Chhau of Jharkhand.

Talking about her reason for doing a doctorate on Purulia Chhau, Bhattacharyya first explained the context: “Purulia, even a decade back, was identified as a politically disturbed area, infused with Maoist insurgencies (a left-leaning extremist movement in India). Attempts to safeguard Chhau not only contributed to altering the fate of the folk practice but also radically transformed the district’s fate, thereby replacing Purulia’s political identity with a cultural one.”

She added that international recognition helped the cause of the dance form. “Chhau dance got inscribed in UNESCO’s Representative list of Heritage of Humanity in 2010, but past two decades of ground work and using this UNESCO accreditation, Purulia Chhau actually managed to get the advantage and got highlighted in global festivals, creating opportunities for the artists themselves,” she said.

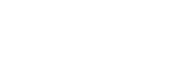

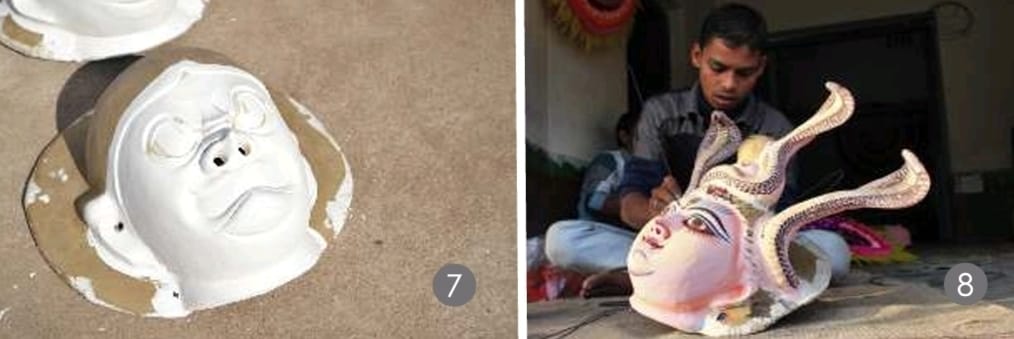

While the dancers win the adulation of the audience, the artisans working behind the scenes have just as much to give. Magnificent and elaborate masks complement the vigorous movements of Purulia Chhau. Mask creation is a complex process, and it sustains local knowledge and livelihoods. In order to support the craft, the Department of Micro, Small & Medium Enterprises & Textiles (MSME&T), Government of West Bengal, in collaboration with UNESCO, has developed a hub of Chhau mask makers at Charida, in Purulia district.

Bhattacharyya told CtoI, “Purulia’s Chhau mask also got accredited with the tag of Geographical Indication (GI) in 2018 and that also helped in strengthening Chhau tourism.”

She continued, “Given the visibility of the folk tradition in socio-political forums, following the accreditations, the content and context of Chhau as well as its impact have significantly changed. My interest in doing a PhD on Purulia Chhau stems from my desire to initiate a dialogue between folk practice, practitioners and practised locale embedded in contemporary socio-political fabric and how once influences the other within the village-art-artist dynamics.”

Elaborating on the economic aspects of Purulia Chhau, the empowerment factor, and its power to drive tourism, Bhattacharyya said, “Purulia’s Chhau dancers as well as the mask-makers belong to subaltern communities. While a decade back, the practitioners were suffering from acute poverty and practising Chhau was more of a passion activity to them, efforts to safeguard the tradition have made Chhau a viable source of livelihood to them now and given them the status of artist.”

Chhau had given the land a status of eminence on the West Bengal tourism map, said Bhattacharyya. “Purulia as a district evolved from a no-tourist zone to attract more tourists than popular destinations in West Bengal like Darjeeling in the past two years.”

“Hence,” she added, “Chhau can rightly be identified as a vehicle of empowerment for these subaltern groups of practitioners and also bring pride to the place, i.e. Purulia, and attract visitors.”

If income improvement comes through the promotion of local culture, it should equally benefit men and women. The gender empowerment achieved through Purulia Chhau is evident in the rise of female dancers.

Bhattacharyya said, “While initially Chhau was a male-dominated art form, at present female dancers are equally competing with their male counterparts, giving rise to around 13 female troupes in Purulia.”

These aspects — socio-political, economic, cultural — made Chhau “a vehicle for gender empowerment and development of indigenous communities”, said Bhattacharyya, adding that her research helped her “explore how culture works as a tool for development”.

On the importance of supporting and promoting folk dance forms, she said, “Folk traditions are cultural expressions and an integral part of life. They’re not just aggregates of the past, but reflect their attempts to keep the heritage component intact while diversifying to include contemporary perspectives. Folk traditions, embedded in roots, can contribute to establishing the uniqueness of a particular society.”

Introducing Purulia Chhau to Singapore

Bhattacharyya held a session as part of the Tapestry festival, where her purpose was to “demystify how safeguarding Chhau contributed to revitalising the fate of the folk tradition and also transformed the fate of Purulia district”.

Her session gave the Singapore audience an overview of “the rich cultural tapestry of West Bengal”, and then moved on to “the intricacies of Purulia Chhau, focusing both on the dance form and the art of mask-making”. The session also covered the different themes, steps, and costumes integral to Purulia Chhau.

“Additionally, I spoke on the impact of Chhau and how it has been converted from a seasonal to a year-round activity. I talked about our organisation’s work in safeguarding the tradition of Chhau and how cultural tourism has prospered in Purulia,” she said. “For example, the first Chhau festival started in Bamnia village in Purulia in 2010 and the first Chhau mask festival started in Charida village in Purulia in 2014 — both were done by us, and now both the festivals are annual festivals of Purulia.”

Referring to the efforts to Banglanatak.com, she said, “Our organisation’s work of safeguarding the Intangible Cultural Heritage of West Bengal (since 2004) is now part of a collaborative project of the Department of MSME&T, Government of West Bengal, and UNESCO (since 2016). The project has been immensely catalytic in safeguarding folk traditions and improving socio-economic prospects of tradition bearers.”