Laxmi Bai, the Rani (Queen) of Jhansi and a leader during the First War of Indian Independence of 1857–58, is remembered as one of the very first women freedom fighters in India. Her intrepid life is still etched in the memory of Indians and she is an inspiration for future generations. Most people know her only for the part she played in the revolt, but her achievements highlight the fact that women are equal (if not better) rulers than men. Her legal wrangles with Lord Dalhousie and governance of Jhansi showcase her intelligence, perseverance and refusal to surrender tamely.

Early Life

Laxmi Bai was born Manikarnika to Bhagirathi and Moropant Tambe in 1827 or 1828. Her mother died when she was very young, and her father served as an advisor to Chimnaji Appa, brother to Peshwa (ruler) Baji Rao II, who was the last of the Maratha peshwas. Chimnaji Appa died when Manikarnika was about three and her father moved to Bithur and became a member of the court of Baji Rao. As a result of her father's position, she spent her childhood in the palace.

Brought up in the household of the Peshwa Baji Rao II, she had an unusual upbringing for a Brahman girl. Growing up with the boys in the peshwa’s court, she was trained in martial arts and became proficient in sword fighting and riding.

A popular anecdote about Laxmi Bai recounts that when she was denied a ride on his elephant by Nana Sahib, she declared that one day she would have 10 elephants to every one of his. While there is no proof, historical evidence shows that she did meet Nana Sahib and Tantya Tope, both of whom became prominent leaders of the rebellion, during her childhood.

She was married to Gangadhar Rao, Raja of Jhansi, in May 1842 and renamed Laxmi Bai in honour of the Hindu Goddess Laxmi. She was Gangadhar Rao's second wife, the first having died without bearing a child.

Marriage

Not much is written about her married life, but what little there is shows that it was as good a match as possible given the fact that her husband was 20 years older than her. She was afforded greater independence than married women were generally given at that time, and her father was allowed to stay in Jhansi with her as well.

Laxmi Bai was an excellent horse rider, and was also said to have been a good judge of horses. It is known that she exercised and practiced with weapons, and famously at some point, drilled and trained a 'regiment' of women to guard the zenana (women's quarters) and even occasionally take part in battles.

Records show that she gave birth to a boy in 1851, who died after four months. In 1853, the Maharaja was persuaded to adopt five-year-old Anand Rao, the son of his cousin, renamed Damodar Rao, on the day before he died. The adoption was carried out in the presence of the British political officer who was given the Maharaja’s will stating that the child be treated as the heir and Laxmi Bai the Regent of Jhansi during her lifetime. The adoption was carried out in accordance with a treaty Gangadhar Rao’s grandfather had signed with the British, allowing the rulers to adopt a child to ensure succession.

Gangadhar Rao died on the 21st November 1853.

Annexation

In 1853, the governance of India was still in the hands of the East India Company, with the Governor-General of India, the Marquess of Dalhousie, introducing the Doctrine of Lapse. The policy called for the British to annex any state whose ruler died without a natural heir, contravening treaties they had signed and precedents of adoption set by many rulers. The Rajas of Jhansi had maintained a pro-British stance throughout their reign, ever since a treaty with the British in 1817 granting Jhansi to the ruling family’s heirs and successors in perpetuity. Gangadhar Rao made explicit reference to his loyalty and that of his predecessors in his will.

Dalhousie refused the Raja of Jhansi's dying request, and, notwithstanding numerous appeals from the Rani, the annexation of Jhansi was declared in early 1854.

Laxmi Bai’s appeals against the decision won support among British political officers and members of the Civil Service, and she consulted a British counsel, John Lang, who was in India, after her first two appeals were denied. This consultation is recounted by Lang in his book Wanderings in India. Lang's account chronicles Laxmi Bai’s famous saying of "Main Jhansi ko nahi doongi” (I shall not surrender my Jhansi).

Her subsequent appeals, including one to the Court of Directors in London, also failed. The Rani maintained her petitions into 1856, her persistence is said to have irritated Dalhousie.

The case of Jhansi highlighted that The East India Company was judge as well as defendant and did not have to answer to any proper court of law. Its implementation of the policy of lapse, showing that it would annex even pro-British states, contributed to the 1857 Rebellion.

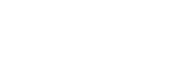

Laxmi Bai was forced into retirement, granted a monthly pension of 5,000 rupees, the palace now known as the Rani Mahal, state jewels and funds for upkeep of Gangadhar Rao’s private estate.

The British rule of Jhansi from 1854-57 stirred up public discontent, with the insensitivity of the political agents, the collapse of the governing court and the imposition of British law creating discontent among the garrison of sepoys as well as the citizens. In particular, the British allowed the slaughter of cows within the town, a move that offended the sensibilities of all Hindus, military and civilian alike.

Mutiny and War of 1857

On May 10, 1857 the Indian Rebellion started in Meerut; when news of this reached Jhansi, the Rani asked the serving British political officer, Captain Alexander Skene, for permission to raise a body of armed men for her own protection and Skene agreed.

On June 5, the garrison at Jhansi revolted against its officers and besieged the British population of the town, who had taken refuge in one of the forts. In response to appeals from the British, the Rani guaranteed them safe passage out of Jhansi if they would abandon the fort. The British surrendered, and the mutineers allowed them to leave the town. Unfortunately, one of the rebel leaders ordered their massacre at Jokan Bagh, just outside the city. The rebels then demanded money from the Rani and threatened to replace her with Sadasheo Rao, a cousin of the late Raja, if she didn’t agree.

The mutineers then left for Agra and Delhi to join up with the main body of the rebellion. Laxmi Bai wrote to the British authorities to report on the situation and asking for permission to form a temporary government in Jhansi to stabilise unrest and allow the town to defend itself. The letters were sent to Major Erskine, who was Commissioner at Sagar. He forwarded them to Calcutta and replied asking Laxmi Bai to manage Jhansi until a new superintendent could be sent.

Laxmi Bai formed a government which included her father and appointed officers and administrators. She had to deal with a coup attempt by Sadasheo Rao, which she foiled, and attacks by the neighbouring states by Orchha and Datia, which she defended against.

The Rani had been sending regular letters to the British authorities but had received no reply. After putting down the mutineers in Delhi and Oudh, the British turned to smaller states like Jhansi. Laxmi Bai’s letter to Sir Robert Hamilton, the Agent of the Governor-General in Central India, went unanswered as the British were determined to conquer the small states like Jhansi to expand British territory in India. On February 14, 1858, the Rani issued a proclamation appealing to all Hindu and Muslim brethren to join the fight against the British rule.

A British force under Sir Hugh Rose, accompanied by Hamilton, marched northwards towards Jhansi, mopping up as they went. Accounts of their march state that they were executing mutineers and suspected rebels with show trials and plundering towns and villages as they went.

In addition, Laxmi Bai was seen as a symbol of the rebellion, with British chroniclers calling her 'the Jezebel of India … the young, energetic, proud, uncompromising Rani, and upon her head rested the blood of the [British] slain, and a punishment as awful awaited her'. Having received no clarification, and knowing of this force advancing towards her, the Rani could only assume, and prepare for, the worst.

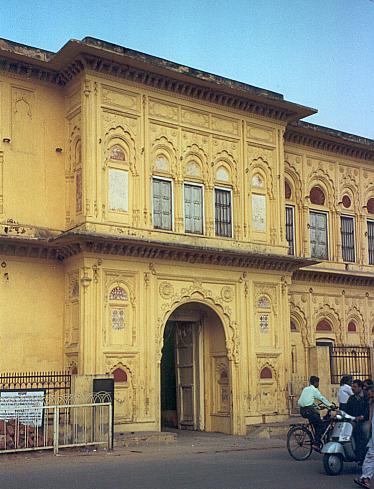

Rose and his forces laid siege to Jhansi and breached the walls after 10 days of fighting. They also defeated an army led by Tantia Tope that attempted to relieve the siege in the Battle of Betwa.

Laxmi Bai managed to escape from the fort with a small force of palace guards. According to legend, she jumped off the fort wall on the back of Badal, her favourite horse, and headed eastward to Kalpi, where other rebels joined her. The victorious British force plundered Jhansi, massacred any man above the age of 16 for four days, and executed the Rani’s father.

After suffering defeat again at Kalpi, the rebels retreated to Godalpur outside of Gwalior. From there, they attacked the fort at Gwalior, which was considered to be the strongest in India and virtually impregnable. They won when the soldiers fighting for the Maharaja of Scindia, who had maintained a pro-British stance throughout the Rebellion, defected to the rebels. Rao Sahib was crowned at Gwalior and Laxmi Bai was famously given a priceless pearl necklace from the Gwalior Treasury.

During the fight against the British at Gwalior, Laxmi Bai was given command of the eastern flank, the most difficult to defend, and met the British at Kotah-ki-Serai on June 17. Most accounts of the battle state that she 'dressed as a man', or as someone going into battle, and also wore her bangles and the pearl necklace.

A majority of chronicles of the events of that day state that she was killed by a trooper of the 8th Hussars who was never discovered. The rebel army is said to have mourned her for two days before cremating her to prevent the British from capturing her body. The British captured the city of Gwalior after three days.

Memorials and Legacy

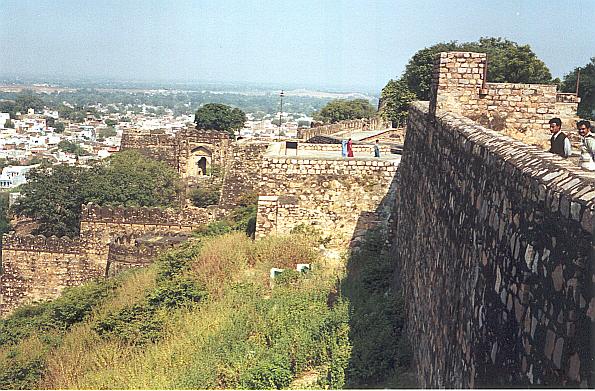

Laxmi Bai’s tomb is located in the Phool Bagh area of Gwalior. 20 years after her death, Colonel Malleson wrote in the History of the Indian Mutiny, 'Whatever her faults in British eyes may have been, her countrymen will ever remember that she was driven by ill-treatment into rebellion, and that she lived and died for her country.’

Equestrian statues of Laxmi Bai are seen in many places of India, which show her and her son tied to her back. Laxmibai National University of Physical Education in Gwalior and Maharani Laxmi Bai Medical College in Jhansi are named after her. A women's unit of the Indian National Army was named the Rani of Jhansi Regiment.

The town of Jhansi is replete with memorials and monuments of the war. The Jhansi fort, from which the Rani is said to have escaped and the Rani Mahal, where she stayed during the British annexation, are the most prominent examples. The Palace has now been refurbished into a museum